The Weirdest Apes and the Distance of Time

A student recently asked me about the Demonic Male Hypothesis; the central idea of this book being that we can perhaps learn more about human sexual differences by studying chimpanzees, our close phylogenetic relations, than ethnographic study of our own species-internal ideas of sex and gender in present human cultures. Depending on the speaker, this may allow or compel someone to consider cross-species data sets in combination with, or even in preference to, cross-cultural ethnographic data points.

I find conversations about comparative primatology fascinating, both as a topic of interest in and of itself, and as a cultural artifact reflecting the assumptions of the day. Public voices like to use speculative work like this to justify any number of sociopolitical ends, a process which as a cultural anthropologist I find interesting. In many respects, plunging an entity like “biology” or “physics” for social models to use is a more creative and flexible act than people realize, or that many would care to admit; the simple fact is that a significantly complex system can be used to justify any number of social positions, owing to the complexity and variability within that system. DNA may not be a literal book, but that doesn’t necessarily stop the bioanthropologist from “poaching in the stacks” of genetic potentialities in much the same way that Michel de Certeau meant when he coined that phrase. We are always moving through the library of human knowledge with certain goals and purposes in mind.

This is getting long-winded, but I felt it should be pointed out. Every time someone tells you a narrative about “how things used to be”, they are also telling you a narrative about “how things should be”, whether they are making an essentialist argument of returning to base or a revolutionary argument about what we must overcome. Either way, I think it is important to remember that you are being told a story; one that though likely true and justifiable in some respects, chose its data points selectively and for subjective reasons. The human biological pedigree is vast and complex, let alone our cultural history, and any number of social models could be found in or justified by the situation various points along the way. Between ourselves and the chimpanzees, our genetic closest cousins, there sit nearly 4 million years of history at the inside, and maybe as many as 11 million years of genetic diversion and cultural invention. Don’t let that number just drift past you. “History”, to you, is comprised of possibly 1/2200th of the time depth since that divergence. And between have been many variations. Strict herbivores, omnivores, and mostly-carnivorous variants. Savannah dwellers, forest dwellers, tundra dwellers. Everything from troupes to tribelets to communist states. Gender-dyadic societies and gender-spectrum societies. Patriarchies and matriarchies both.

And let us not forget the physical differences; an adult human is so physically different from an ape that neotony has been suggested to explain our seeming lack of a meaningful final adult growth spurt. We don’t have an estrus cycle, alone among the primates. We usually have the largest male sex organs as well as the largest mammary glands in the entire order. We otherwise also present the least overall sexual dimorphism, to the point that forensic anthropologists frequently mis-type sex, at a rate that would be inconceivable within a gorilla assemblage. So not only does biology allow for critique of cross-species analogies, sex and gender are areas in which biology should be warning us to be especially cautious; sex differences are one of the things that make us the most anatomically distinct from our cousins, not similar. And the other major difference, our brains – a chimpanzee peaks with mental equivalency to a human toddler – means that our extra-cranial anatomy may have much less influence on an individual’s life than it would for any other primate. Chimpanzees, too, in turn changed greatly over time and no longer resemble our presumed common ancestor in closely analogous fashion; as we became dissimilar to them, they were also becoming dissimilar from us, in different directions for different reasons. Nowhere is this clearer than in studies of chimp-human cohabitation cases and experiments; our social instincts diverge from chimps qualitatively, not just in degree.

“Nim” the Chimpanzee (source:NPR)

“Nim” the Chimpanzee (source:NPR)

I am not saying that one shouldn’t make observations or suggestions based on comparative primatology. We can, and do, and especially when we find that the entirety of the primate order holds something in common, the cultural anthropologist gets very interested indeed. We are apes ourselves, and despite our distinctive qualities as a species, our heritage shows its face somehow or other in nearly everything we do (and not just the primate portions of it, read “Your Inner Fish” sometime if you want your paradigm shook up a bit). But the natural limitations of such analogies should also be considered, and we are justified in always asking about the motivations of a given theorist when they highlight this fact from this cousin at this time rather than another.

Some thoughts on the Science of Princes

“A map says to you, ‘Read me carefully, follow me closely, doubt me not’. It says, ‘I am the earth in the palm of your hand. Without me, you are alone and lost.’ … Yet, looking at it, feeling it, running a finger along its lines, it is a cold thing, a map, humorless and dull, born of calipers and a draughtsman’s board. That coastline there, that ragged scrawl of scarlet ink, shows neither sand nor sea nor rock; it speaks of no mariner, blundering full sail in wakeless seas, to bequeath, on sheepskin or a slab of wood, a priceless scribble to posterity. This brown blot that marks a mountain has, for the casual eye, no other significance, though twenty men, or ten, or only one, may have squandered life to climb it. Here is a valley, there a swamp, and there a desert; and here is a river that some curious and courageous soul, like a pencil in the hand of God, first traced with bleeding feet.” ~ Beryl Markham

Cartography has been called the “Science of Princes”. It’s a reference to the power that a map-maker has to represent reality in a way that suits them. The mystique of the written word – or graven image – is that it seems to connote objectivity on an idea. By being passed around independently of its author, a word suddenly seems less reliant on your opinion of them, especially if they are now unknown. A map in an encyclopedia might as well be scriptural. And such a map in the hands of a ruler can effectively change a legal reality or even people’s self perception. I accept without much thought most of the time that I am a “Californian”, for instance. Is that because of the political reality that coercive power could be exerted against me if I, say, refused to pay taxes to the state? Well, maybe a little! But I bet the maps of the state that are ever present, that we are taught to recreate with crayons and macaroni noodles in elementary school, are as much if not more effective at reifying the concept of state-as-place. I’ve known plenty of people who couldn’t so much as name the state capital, but never anyone who did not know what “state” they are in.

And yet, statehood is far from an objective, eternal truth. For a natural cultural or ethnic category, the state boundaries are suspiciously… linear. Which of course means that they are nothing of the sort. Oftentimes there are conversations about “splitting” the state between North and South, or into even smaller pieces. But again, no one questions whether the state exists in the first place. How could it not? It’s on a map. And maps must be fought with more maps. Or counter maps, as is sometimes said.

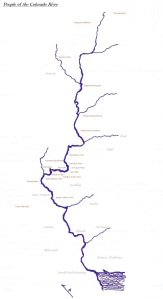

I’ve been thinking about the power of maps this week because I’m working on drawing one for the blog. You can see a rough draft below. I thought I’d get it done sooner and have it ready for the week’s update, but in lieu of this, I thought I might write a few notes on mapmaking and the problems that come up whenever you set out to represent fluid social and political realities in the seemingly concrete medium of the drawn map. The general idea was to represent the traditional peoples of the Colorado River, absent some of the manipulations of hydraulic engineering and reservation politics that have redrawn the map since the historical United States started coloring over the lines.

One challenge I’ve been facing is how to represent nationhood when it is not tied to land. We’re so used to seeing maps with clear boundaries, the natural assumption is that one should find a way to create them. Even a cartographer who is mapping out vegetation, or average temperature, will find a way to draw thick, definite lines in between them if they can, as though the manzanita bushes hit an invisible wall at some point, ceding their ground to the scrub grasses without argument. It’s interesting how satellite mapping messed with this assumption, and how GIS rose up to conquer the issue (among other useful things!) essentially by drawing lines over the landscape as needed to help the eye make sense of the mess.

A survey of the internet reveals a host of solutions to similar problems. Sometimes “tribal” territories are drawn out as though they were actually nations. It’s not the worst idea. Sturtevant’s grand map of the Native American world is an excellent resource and I’ve certainly been referencing it quite a lot lately. People are naturally curious about “who lives/lived here” and such a map gives you nice, well defined boundaries that you can find yourself within. Many modern maps, like Sturtevant’s include the outlines of the modern states, which is part of what made me start thinking about statehood in the first place. It’s obvious, of course, that the state boundaries correspond to no pre-Anglo reality whatsoever. Yet we still include them? Partly, I assume, to help the viewer orient themselves. But it also implies that states are somehow timeless realities, or at least natural realities. But are the Cocopah “Mexican”, because their homelands now are? The situation of the Yuma, Cahuilla, Kumeyaay is also tense, split midway across and separated family from family by the illusory border- and the crime and poverty it generates. Even inter-state borders can have serious implications. Political inertia was an important factor, for instance, and lack of representation, but I still doubt very much that the loss of the Paiute Strip could have occurred so easily without the arbitrarily imposed boundary of Arizona being thrown into the mix.

So perhaps we should be less concerned with lines. I certainly decided early on that I had no interest in maintaining the modern state lines. The unifying force I wanted to look at was the river itself, not the modern political boundaries it now flows through. That leaves you with a question of representation, though. Do you replace the modern lines with ancient ones? Or just leave the names floating in midair, landless? Drawing them could imply something very untrue, because band politics are fluid, and travel “across the lines” was commonplace. It was not fee simple ownership by any stretch, and many place were communal property depending on circumstance; important locations would be used by many people, and the further south you go, the more often this is true of the Colorado River itself, which everyone needed access to and often got, even across sometime battle lines. Further up, you have the Grand Canyon, critically important even to groups from very far away who had their own means, their own secrets, their own kinds of ownership within the canyon walls. Often, I find that specific places are more important than general land area, that the annual migration of a group, though the exact opposite of aimless, was “along a path”, not “through our territory” necessarily. A ball and stick diagram might be more appropriate for the realities of transhumant foraging- but it would be a bit confusing to draw some nations as a ball and stick and others, like the Puebloans’, justifiably as more traditional, blobby Western-style polities.

So I can be excused, I hope, for leaving off lines altogether. But this, too, could have some unfortunate implications, falling into the western myth that the land was unowned or “unorganized” until it was mapped by Whites. It was nothing of the sort, and specific places and resources were always under the control of one group or another. It wasn’t “ownership” as such, but it would be wrong, all the same, to describe the land as “unowned”. The whole language of owned and unowned is simply inadequate to describe the realities of pre-Anglo land tenure in the Southwest. I’ve settled on a lineless map, for now, but I’m not necessarily happy about it. I might be thinking about some other strategies for representation as I go along. One way I tried to compensate was to be as faithful as possible to language. Nomenclature in my presentation follows the most “local” as best as I was able to reckon it. Paiute names, if I could find them, went to Paiute places. Limited, unfortunately, by the loss of many of those names over the centuries. In a few places, I decided not to map something at all rather than use a crude English renaming or speculate too much on a past situation. Another thing I would like to do in the full map is to include as many important landforms as possible, since they are often more important than boundaries per se. But again, the loss of information hurt a great deal. I could find few good sources for the stretch now in Mexico, for instance, and it hurts, knowing that loss of information corresponds directly to the loss of people, bands, and even nations.

Draft number one is below. I’ll be posting some much bigger and better maps as the project goes forward, hopefully with some more notes and thoughts on how they were crafted and what they show us.

The Evolution of H. religiosus

It became trendy in the late 90’s to describe humanity as Homo religiosus, with varying degrees of seriousness. It’s meant to point out both the particularity of human religion within the animal kingdom, and perhaps even the importance thereof in defining us. It’s not entirely unwarranted. After all, religion seems to be very nearly a human universal. No living society lacks it altogether, and until quite recently there seemed to be no real challenges to the dominance of religion in social and political life, even in cultural areas where society and politics are very diverse and variable in form. Anthropologists have long been interested in the subject for obvious reasons, but actual theoretical advances in the study of religion have been funnily sporadic. It makes a difficult study subject for a number of reasons, not the least of which that it is nearly impossible to approach religion without one’s personal bias getting in the way. For the past century, most anthropologists were atheists or agnostics, with a vested interest in creating a conception of religion as something inherently containable and replaceable; a superstitious area of life performing only certain functions easily replaced by modern science and economics. In the social sciences generally, an idea called the Secularization Hypothesis reigned from the beginning of the century until the 1990’s. Part and parcel with the concept of modernization, it posited that the then-overwhelming inertia of governmental secularization would eventually spread to all other areas of life, replacing the traditional roles of religion.

However, whether or not this hypothesis might eventually be proved true, a century has gone by without this hypothesized future becoming a reality. Indeed, in most parts of the world as it now exists, religion seems to be radicalizing and gaining in political power by leaps and bounds. Globalization certainly opened up the world for new kinds of exchanges of religious ideas, but aside from a few nations in Europe and North America, the idea of even governmental secularization has not caught on in very many places, to say nothing of the idea that religion itself might die. Instead, it is reinventing itself in a thousand ways, a potent social force of its own accord even as the double challenges of globalization and capitalization also change the face of the world in myriad ways.

So it seems that we remain Homo religiosus for the time being. This raises a number of questions for an anthropologist. One of them has to do with origins. Even phrasing it as H. religiosus suggests the long view of our natural and cultural evolution. Yet, there are more mysteries than answers where this long history is concerned, up to and including just how long that history might be. Whenever we encounter a seeming human universal, we start to get very curious about when and where it started. Was it something that originated in our primeval past? A more recent concept that just turned out to be uniformly popular? There are only a handful of true human universals, and they are of special interest to those researchers who are interested in how culture and evolution interacted in the formation of our species. Whether or not we are H. religiosus, religion certainly seems to be strongly tied to the character of H Sapiens. But how strong the tie might be is another question, and one with implications for both our past and our future.

Can we trace religion backwards in time? A little bit. We start seeing planned burials 100,000 years ago (possibly much earlier depending on who you ask, but Skhul cave in Israel is the earliest undisputed end point, since the individuals there were gently interred with jewelry and ochre paints). We start seeing apparent depictions of the supernatural in objects and paintings from around 40,000 years ago. We also know from our observations of the natural world that the other primates lack anything like the social institution of religion as we generally understand it, so it seems likely that religion postdates our evolutionary separation from our closest cousins. These, though, are questions of “what”, they don’t help as much as we might hope with questions of “why”. So, actually explaining the “why” of religion remains a mostly speculative dialogue, with many parties and many assumptions. Below, I’ve grouped the most common explanations for religion into six basic categories. Some of these are emic, or insider’s, perspectives on religion popular among religious folk themselves. Others are purely products of the secularized Western academic world, imposed by the researcher’s perpetual need for objective descriptions that don’t require specific beliefs to work.

Skhul cave, site of the earliest good evidence for the existence of human religion (photo source: R Yeshurun, Wikimedia.org)

1. Collective memory

2. Revelation

3. Deduction

4. Evolutionary psychology

5. Traditional psychology

6. Community

Sympathetic Magic: John Frum and the Political Theology of the “Cargo Cult”

If you’ve never heard of a cargo cult, it’s a religious movement endemic to the Pacific island of Vanuatu that did a good job of capturing the imagination of Westerners: the kind of thing that so aligns with what we already believe about “primitive people” in other places far away that it instantly and easily slips into our worldview without much critical thought. It’s the kind of story that people remember from their Cultural Anthropology class, long after they forget all the boring theory and terminology surrounding it. In the popular, stereotyped mythos, natives living in the jungles of Vanuatu during the 2nd World War were mystified by the parachuted bundles of “cargo” that dropped around the airfields. After the war, they started a cult around the bundles, building elaborate imitations of American airfields, complete with pretend radio towers and air traffic controllers. In doing so, they hoped to induce the “cargo” to return. It is something of a “just so” story, often used to demonstrate a basic anthropological concept which I’ll get to later in this article, or in less scrupulous hands, to demonstrate the folly of imitating what you don’t understand it; famed physicist Richard Feynman coined the term “cargo cult science” to refer to pseudoscientist types who produced sciencey-sounding papers but failed to back it up with replicable research. Like most such stories, it misses quite a few shades of the truth. In anthropology, we have our own derived term, “cargoism”, to refer to the phenomenon of turning real events into ridiculously biased portraits of exoticism. The movement is a real faith, though, and one which is still practiced in Vanuatu.

For actual practitioners of this religion, the faith revolves heavily around the actions of a mystical prophet, who went by the name of John Frum. Accounts differ, but most sources agree that John Frum was a black American serviceman who appeared among the people to promise them wealth and prosperity if they were to reject the French and British missionary projects on the island. His followers abandoned the missions en masse and regrouped in the mountainous regions, where they revived many of the old traditions of the indigenous population along with new ceremonies introduced by John Frum to bring about Western prosperity without submitting to the invading Americans and Europeans. The missionaries feared that this would become a violent rebellion, and in 1941 arrested a native claiming to be John Frum and several of his lieutenants, exiling them from Vanuatu to other European properties and attempting to stamp out the movement. After the war, it was said that John Frum had gone into the volcanic Mount Yasur to commune with the ancestors of the people, and that he would one day return, bringing with him abundant gifts from them, the much coveted goods of the Western nations. The cargo rituals that so fired Western imaginations began soon after the war, and though they were never the central goal of the movement, they are continued to this day along with the other activities and ceremonies of the movement. They have continued to be a force in Vanuatu political and religious life, and steadfastly opposed both nationalization and Western political subordination generally. John Frum, as a symbol, represents a best of both worlds; a soldier, but black like the natives, a bearer of Western gifts but not Western domination. He is the manifestation of the traditional past, the Westernized future, and a present that therefore leaves room for cultural pride and political autonomy.

There being no record of an American serviceman by the name, it has become popular among many historians to say that he never actually existed. Many modern practitioners say that he was effectively real, but a manifestation of the will of the ancestors, a viewpoint not dissimilar to Docetism in early Christian history. I am inclined to think that John Frum was a real person. It’s not so implausible unless you make the assumption that to exist he must have really been an American airman in order to be real– I think it is quite likely that he was a native, perhaps even the very man authorities eventually arrested, and an airman only in the sense that the ritual airfields are airfields. Certain people in any population are temperamentally inclined to take leaps of intuitive logic like those that our hypothetical John Frum seems to have made. Rather than slowly constructing a logical path from A to B, people of a certain temperament prefer to gather as much data as possible, then make a sudden jump to a conclusion based on that information in a way that they feel is right but cannot necessarily explain. Those who take Meyers-Briggs personality theory seriously may recognize this as a trait associated with introverted intuitives, or as one of the Jungian “functions” of the mind that are represented to various degrees in many but not all individuals. For our John Frum, or whoever helped create the mythos of John Frum, it was a simple matter to take the whole military and colonial occupation as a whole and realize correctly that there was no necessary connection between the benefits and the costs of interaction with Westerners, that by learning to imitate the habits of the interlopers, the rewards could be got without agreeing to sacrifice the entire past and identity of the islands.

And this John Frum, whether or not his name was really John Frum, actually got quite a lot of the story right on. Airfields are a necessary precursor to planes, and all of the elements of the cargo rituals really are necessary to the functioning of airfields. Their landing strips would certainly be serviceable enough; even as a fully equipped airfield, if only the specific elements of technology (like radio) that were not available to them for a host of reasons, not the least of them intentional efforts by colonial administrators to keep them out of native hands as much as possible.

The idea underlying the rituals also demonstrates another principle that is universally found in human cultures, though my students tend to have a harder time seeing it in their own: imitative magic. Imitative magic is sort of badly named, since “magic” connotes to most English speakers either charlatans pulling rabbits out of hats or Satanists and/or Harry Potter performing dark rituals in the dead of night. To an anthropologist, it’s a much more general term that. Any attempt to manipulate outcomes in the natural universe through the use a ritualized pattern counts as magic. Praying to God that you’ll do good on an exam is working magic by the anthropological definition, since it uses a cultural form (the structure of a prayer and the expectations you have about its efficacy) and has an intended real-world effect. So is washing your hands to prevent catching a disease, or taking an aspirin to alleviate an illness you’ve already got. As long as those two elements are present, a cultural form to follow and the expectation that it will work to change something in the physical world, it counts as “magic” as we define it.

Imitative, or sympathetic magic is a specific variant of magic that follows the principle of “like creates like”. This is how most medicines work, especially vaccines- they imitate the disease they mean to cure as closely as possible without actually being that disease. These days, we know a lot more about the biochemistry of medicines and what makes them more or less effective from a scientific standpoint, but we’ve been using the principle of like creates like since long before we could scientifically describe it. This is one reason pharmaceuticals make a small business of going into far-flung villages and asking local healers what plants they use- they know there is likely a grain of truth to at least some of their remedies, so they want to hunt down those plants and test their potential to become the next wonder drug. This practice is sometimes called bioprospecting.

Not all imitative magic is medical, though. We often use it in social situations, for instance. Acting calm because you want someone else to calm down is a good example; while this is not necessarily magic in the sense that it is a practical solution that anyone might come up with on the fly, the specific ways that we act when we are “acting calm” are specific to our culture. Someone trying to do it is likely to imitate scenes that they’ve seen on TV, or the way they remember their parents trying to calm them down, or as in the case of a recent news story, following the advice of a church sermon. The point is that we are following a cultural pattern which says “if you follow these actions in this order, the specific outcome you want will come about”, which makes it magic, and the logic of “if I act out what I need, it will come true in reality”, which makes it imitative. Another good example of imitative magic is advertising: someone who posts a billboard of a person happily munching on a burger is hoping that you will be respond by ordering a burger (imitating the prescribed action) in order to feel happy like the person on a billboard (the desired real) outcome. At the same time, the advertiser themselves is hoping that their action (putting up a billboard of their product) will result in an effect in the real world (people buying that product). It works more often than our dignity would like us to admit.

So does the magic of the “cargo cult” work? Well, that depends on how you look at it. If you talk to an islander today and ask why they are still waiting for John Frum’s return, they will wryly remark that they have only been waiting fifty years for their messiah, while most Americans are waiting for one two thousand years overdue. On one level, a goal of the cargo cults was to create cargo by the imitative magic of the airfield rituals, and this has not yet come to fruition directly, though there is certainly much more material wealth on the islands now than in the 1950’s. On another and I would argue more important level, the movement was an attempt to revive traditional religion and free the people of Vanuatu from the imperializing message of necessary cultural extinction. John Frum was a revolutionary message by his mere existence, and remains a powerful symbol of a different mode of advancing into the future outside of the colonizing thumb of the Western powers. His followers, now a political party in the national government, have endeavored to make this dream incarnate. John Frum provided a means of ritually creating a facsimile of a future that the people of Vanuatu could respect and even desire, and in so doing, paving a way for a different kind of destiny for his countrymen. In this latter goal, it seems to me that he was as successful as any of us can reasonably hope to be.

Coombs Village: Anatomy of a Pit House

This June, I had the opportunity to visit a place that I had heard about but not been to myself– Anasazi State Park in southern Utah. The park is within the boundaries of the modern town of Boulder, Utah (not to be confused with the much larger city of Boulder in neighboring Colorado) and exists primarily to preserve a massive archaeological site known as the Coombs village. It is a well-preserved site with a brief but interesting history, settled by Virgin Branch people around 1160 CE and abandoned along with the rest of the nearby area around 1230 CE. There are signs that it was used as a seasonal village site from a much earlier date, but during that time, it was a permanently occupied town with an important role to play in the politics of the region.

We’ve learned a lot more about that political history since the initial excavation of the site in 1958. At the time, the priority of the researchers was to document the archaeology of the region very quickly in advance of its inundation by the Glen Canyon Dam, then under construction. They missed some significant facts. In the 1950’s, there were only three well-known archaeological cultures in the Southwest: the Puebloans, or Anasazi, who occupied the Four Corners region, the Mogollon of northern Mexico and New Mexico, and the Hohokam of Southern Arizona (and even the cultural distinctiveness of Mogollon was still disputed by some). This meant that any large sites found above a certain meridian were simply assumed to be Puebloan, including this one, which was assigned to a large subset of Anasazi called the Kayenta Branch.

Coombs village is indisputably a Puebloan site, but the Puebloans were not, as it turns out, the only vibrant and influential culture in ancient Utah. Starting as early as the 1930’s, some researchers had started to notice some distinctive patterns of rock art and basketry that were unique to central Utah, which they named the Fremont Culture. In fact, one of the early proponents for the Fremont, Jim Gunnerson, visited this site two years ahead of the major excavation, but passed it over, seeing that the artifacts piled on the surface of the “Boulder Indian Mound” were clearly Anasazi and therefore unimportant to his thesis.

However, as the decades marched on, the portrait of the Fremont has become clearer and more compelling. Many large sites have been identified and still pop up periodically as more and more of Utah is disturbed by construction projects, and along the way any doubt as to the existence of Fremont Culture has dissipated. This has had some interesting implications for the Coombs site, which as it turns out was right on the frontier between the Fremont and Puebloan culture areas. Like many Southern Utah sites, it contains artifacts from both cultures, and even structural evidence of cultural mixing.

One of the elements that gives it a Fremont feel is the pit house depicted in the photo above: though above-ground stone pueblos were the norm for Puebloan peoples after the 9th century, it might be fair to say that pit houses are the more standard form of dwellings in the US Greater Southwest. The ancestors of the Puebloans, a culture known as the Basketmakers, dwelt in pit houses that looked much like the one in the photo above, and they continued to build them occasionally in some areas, one reason why the excavators did not find it especially remarkable when they unearthed one at Coombs village. Here, though, we might consider it part of a pattern in the record, because the Fremont also dwelt in pit houses.

What is a pit house? It’s actually a catch-all term for any partially subterranean structure found archaeologically, which makes them a little bit tricky to define. Partially submerged dwellings are a sensible response to dry and arid environments: they stay cool in the summer, warm in the winter, stable in the wind. They are conducive to safe storage, and are quicker to build than the massive stone cities that later became the norm in the Southwest. Because of this utility, we find pit houses in cultures spanning the globe, and in particular the plains and desert regions of the United States. At the time when the Puebloans were most prominent, their neighbors to the east, north, and south, still relied on the basic idea of the pit house, and the Puebloans themselves retained a specialized form of underground structures called kivas.

Most pit houses, in both Fremont and Basketmaker, were relatively large one- or two-room structures, with a central hearth and storage niches ringing the walls. The submerged portion is sometimes lined with stone to keep out moisture, sometimes just plaster. Four or six larger pilasters hold up a sloping roof, which was then sealed with branches and mud. A hole in the roof provided ventilation for a fire, which kept the dwelling warm during the surprisingly chill desert winters (these hills do fill up with 30 inches of snow, some years). Entry was through the roof via a ladder in single-room structures, or sometimes through a narrow antechamber to one side of the house. If there was no antechamber, a chimney of sorts was still needed to ensure a flow of air. In the photo, you can see a hole in the wall near the ground, indicating the location of this chimney. A slab of rock sufficed to prevent the air current from extinguishing the fire. A standard pit house comfortably houses around six people, though they varied in size and the numbers they could accommodate.

A kiva, unlike a pit house, was perfectly round, and became more and more stylized as time went on. Modern kivas in Pueblo towns are exclusively used as religious and community centers, a place for important rituals and events for the town or clan. They are sacred space, and every part of the kiva represents spiritual concepts and purposes. It’s not really clear when and how the transition from pit house to kiva took place in Puebloan history. Kivas were probably dwellings originally as well, like pit houses, as there are sometimes clear signs of occupation inside. By the end of the Puebloan period, though, it is clear that at least some of the spiritual and ritual importance of these rooms was evident, that they were more than just living spaces, and probably reserved for special uses much like their modern incarnations.

Less interest has been taken in pit houses themselves, and I think this is a shame, since understanding them is understanding the life way of many peoples, at most times in Southwest history. There are many locations where one can take a tour of a kiva, but fully reconstructed pit houses are uncommon. In fact, the only other locations I can think of off hand to even see an excavated and rebuilt pit house are at Step House in Mesa Verde, and one at the Crow Canyon Archeological Center nearby. That is one reason why Anasazi State Park is and remains a treasure well worth a visit if you are ever in the Escalante region. The great stone pueblos remain evocative monuments and an important legacy (and you can also take a look at some of Coombs’ reconstructed Pueblo-style room blocks, as shown below) but pit houses are important, too, and a gateway to understanding the interactions at this frontier village caught between two cultural traditions in a shifting and perilous era.

“Captain, it’s Just Like Earth”- Anthropology across two generations of Star Trek

I often recommend science fiction classics to friends and students when talking about anthropological concepts. Considered thematically, the goals of a writer of space operas is not really very different from the work of a social anthropologist: By momentarily stepping outside of the normal subjective experience of humanity, we seek to better understand it. Science fiction writers step off of this planet for inspiration… but never too far. Often science fiction plots occur in a universe with no extra-terrestrial life at all, such as Asimov’s Foundation series or Herbert’s Dune. Others have alien or robotic existences, but those aliens are often very similar to us in most significant respects. Robots who want to be human and struggle with the existence of emotions, bird-creatures with sociopolitical structures suspiciously similar to that of 20th century Russia, intergalactic warlords who suffer from bipolar disorder. This is because a story about a truly alien life would be, aside from incomprehensible, also irrelevant to what most writers embody as their real goal. We want to understand why we are the way we are, even if the means for doing so takes us into the great unknown.

One consequence of this is that science fiction writers are very often conversant in the literature of anthropology or psychology, having at least a layman’s understanding and interest in what’s going on in their environment. An interested student could scarcely find better introduction to the Ecological Anthropology school than a reading of Dune, for example, and it is no accident considering who Herbert was friends with in real life. There is thus a flow of ideas, and it probably goes both ways, as with anything in popular culture. So I wondered, what could we learn about thought in the social sciences by watching Star Trek? The first thing that crossed my mind is that the writers of the show have had to confront the above fact- that science fiction aliens have a tendency to look and act rather a lot like humans- directly and in a way that would allow for suspension of belief on the part of the audience. How they accomplished this tells us a little about the zeitgeist of the social sciences across time.

Unlike a book, a television franchise lasts a very long time, and episodically; the nature of what’s presented on screen is going to evolve, and in the case of Star Trek, it evolved alongside sixty years of changing thought about the social and biological sciences. Another consequence of television is that having human-like aliens is a requirement more than a preference. Especially in the early years, sci-fi show budgets did not allow for elaborate special effects or even creative attempts at costuming and makeup. “In those days”, William Shatner laments in his autobiography “You wrote to a supply house for some alien costumes, and a few weeks later you got some random rubber monster suits”. If they wanted to go down to a planet, the budget problems were worse; it was either a styrofoam quarry, or some excuse to borrow a set from a historical period piece. Nor would producers (or audiences, presumably) green-light a character (especially a protagonist) so unhuman as to be unsympathetic. Mister Spock of the original series very nearly failed to exist, and his design was changed considerably by these concerns. Star Trek abounds with non-humans who are either aspiring to be human or dealing with the reality of already being part human, from Spock to Data to Seven of Nine. But even among aliens who are not main characters, there is a definite tendency for sentient alien species to be bipedal, bodily hairless, possessed of human-like cultures and personalities. Indeed, even in more recent outings such as Star Trek: Enterprise, it can be hard to distinguish between aliens and humans without looking at their faces. TV Tropes refers to these as Rubber Forehead Aliens and notes their tendency to predominate in science fiction plots. Not only are there very similar species on different planets, but very similar societies. Planets just like earth have human-like people in American desert-like dusty playas, living in Old-West like towns with cowboy hats Just Like Ours.

For writers, however, this also creates a problem: Why would another planet or another species just so happen to look or act like us? In order for an audience to suspend belief, some explanation (if not necessarily a good one) is needed. The answer of the original series was to delve into the serious social science of the day. One of the answers that sociologists and anthropologists were offering at the time was convergent evolution.

At the time, anthropologists and biologists were asking a lot of questions about evolution, and how it might apply to culture. One of the outcomes of anthropology’s broad spectrum of interests is that most people trained in the discipline know a fair amount about human evolution, itself a new science when anthropology began. Many biologists and anthropologists early on thought about evolution as a progressive, linear process, in which animals gradually gained in complexity over time.

In such a light, it made sense to posit, in creative moments, that evolution might take a very similar course of action in more than one place, since evolution itself was following a logical blueprint of sorts from most simple to most complex. There are even some examples of something like this happening in real life; animals that have adapted to fill similar ecological niches often display morphological (body shape) similarities. A classic example is the Tasmanian dog, a canine-like animal that evolved on the Australian island of Tasmania. It’s largely unrelated by heredity to the dogs non-Australians were familiar with, yet at a glance looks very similar and performed a similar ecological role.

In the 1960’s, many anthropologists were excited by the possibility that such convergent evolution could also be possible in human societies. Just as biological species evolved along a logical progression from simple to complex, perhaps cultures did as well. Students at many schools are still taught the basic outline; foragers become pastoralists, pastoralists, then became agriculturalists, then became empires. Since it was the ethos of the day to assume that Western culture was the most “complex”, that meant that every society in the world was destined to become “just like us” eventually. So why not a whole other planet? This assumption underlies not just the plot, but part of the underlying ethos of the Star Trek universe. With the Prime Directive, the Federation, like the Cold War era nations, assumes that cultures inevitably evolve into something akin to themselves, signalled by a change in technology.

However, in both species and societies, convergent evolution in the sense that Star Trek assumes is unlikely, at least to the degree that it occurs in that universe. Canines and Tasmanian dogs may look somewhat similar, but in terms of biology, there were significant differences. Tasmanian dogs were marsupials, not placental mammals, carrying their young in external pouches for some time after birth. They certainly could not interbreed with dogs, as different alien species in the Star Trek universe do with each other. As the ethnographic record filled out, it seemed less and less likely that cultural evolution converged in the same way either. Westernization looked more like a story of conquest and subjugation than pre-ordained evolution. Societies are not unknown to make choices opposite that which unilineal cultural evolution suggested, often for reasons that were perfectly logical from their perspectives- the peoples of the American Southwest intentionally abandoned a state-like system for the more egalitarian pueblos, for instance, and many cultural practices in the historical Southwest seemed aimed explicitly at preventing the centralization of power. A similar process may have occurred among the Maya following what Westerners called the “Classic Period”, one thesis of Jared Diamond’s popular text, Collapse.

The upshot was that by the time the sequel series Star Trek: The Next Generation came out, the “just like Earth” planets were seeming less and less plausible, even for fans with only a casual knowledge of evolutionary science. Biologically akin species evolved separately on two different planets seemed unlikely, and the development of almost exactly similar cultures increasingly seemed, well, not like Earth at all. Serious fans of the show were picking apart the science of the original episodes with fervor. If they were going to continue to save money on alien face masks, a new conceit was needed.

The answer was found in a new debate that had by then taken wing: how life originated in the first place. By the time the 20th century dawned, oppositions to the conventional description of evolution were disappearing. However, the question of how life had actually appeared in the first place remained largely a mystery, and is still an unresolved question if not to the same degree. Life seemed to just suddenly appear in the geological record, and the biochemical path from non-life to life was non-obvious. One suggestion was that rather than naturally evolving here, life had somehow migrated here from somewhere else, perhaps via meteorite impact.

In the TNG episode “The Chase”, this theory was advanced by a Federation scientist, who posited that rather than simply showing up through evolutionary coincidence, the principal species of the Alpha Quadrant had in fact been “seeded” by an already existing race of lonely humanoid aliens, implanted along with certain genetic instructions to make the eventual convergence less a coincidence than a design. This leads to a tense standoff as multiple parties rush toward the uncomfortable truth, leading to one of the most intense lichen-collecting expeditions in television history.

For the time being, we seem to have reached a hiatus in new Star Trek TV series, despite the popularity of the “reboot” universe movies now selling tickets at the box office. Science, however, has continued apace, and we know much more than we ever have about the origins and nature of life. From punctuated equilibria to cladistics to mtDNA, the science of biological evolution becomes clearer with each passing year. Anthropology, tempered by waves of postmodern revision, has entered an era of more and creative fieldwork, less racist assumption, and outlines of more complex multilineal theories of social evolution. Perhaps the next time a network series shows up with a “forehead alien” in need of explanation, we’ll be ready with another fascinating set of theories to offer them. And with a bit of luck, it may even be that both fiction and nonfiction worlds will grow closer to our mutual goals of truth and self-understanding in the process.

Orpheus’ Wife: Dying and Returning Spouses in Folklore

Anthropologists have a longstanding love affair with folklore. The study of folklore is a discipline of its own accord, one which attracts researchers of many different backgrounds, so not all folklorists are anthropologists. But most anthropologists have a keen interest in the stories and songs that are passed down from generation to generation about the way things used to be. Many early compendiums of folk culture across the world- Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, William Graham Sumner’s Folkways– are even considered formative to our discipline, and to our sister field of sociology. Moreover, stories can be important for a number of reasons, and to anthropologists of all stripes. Stories are a storehouse of information about the past, which archaeologists can use to flush out our understanding of the past and resolve quandaries. They are an expression of deeply held religious and ideological assumptions, which can help symbolic and cognitive anthropologists figure out the interior life of people in a given culture. They are often exemplars of oral tradition, which help linguistic anthropologists understand what a language looks like when it is “done right”, and how it has changed over time.

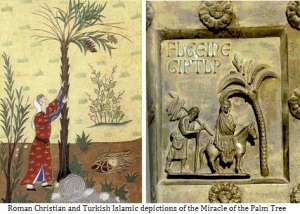

For cultural anthropologists in particular, it is interesting to note and compare things that are the same from place to place. There are many genres and even specific tropes and motifs that appear in the mythology of many cultures. Sometimes this is because the same story has been passed down to more than one culture from the same source. For instance, there are many stories told throughout Europe about the medieval emperor and conqueror Barbarossa- some vary wildly, or even contradict each other at points (he is “buried” in many different places!), but all stem from the exploits of the same real person recorded in history. Many modern Muslims are quite familiar with the story of a miraculous palm tree that sprung forth with water and fruit to help Maryam (Mary) when she was carrying Isa (Jesus) in her womb through the desert, but more Christians might be surprised to learn that this was a story commonly known to Christians of the time, illustrated in Christian artwork and writings as early as the 6th century:

However, not all mythic similarities can be explained the same way. Sometimes, the same motif is found in the stories of cultures separated from each other by vast distances of time or space, distant enough that it is unlikely they are telling the same story, yet are found telling stories with interesting similarities. Stories of great floods, which inundate the world and leave only a survivor or several survivors left to repopulate the world are common throughout the planet. Many are familiar with Noah’s flood in the Hebrew and Muslim holy texts, but similar stories are found in Asia, North and South America, and Africa. In many cultures, there are a pair of heroic twins who do important deeds at the beginning of the world. These are especially common in North America, but like the flood narrative, variants are found in many places around the globe.

How can we explain this kind of coincidence? One explanation is that these stories explain or express concepts that are human universals, so one would expect them to show up again and again in different forms. Floods occur everywhere, for instance, and all cultures must deal with the loss and unpredictability of such events. It’s not necessarily surprising that, when considering the past, multiple societies might imagine an even larger event to explain why things are the way they are, or remember a literal flood in apocalyptic terms. Identical twins have always captured the interest of others, who want to parse out the ways that they are similar or different in personality, so they make a natural context for stories that wish to similarly explain the similarities and differences possible between people as a whole. The differences, though, can be as informative as the similarities. Every society has its own contributions to make, even to a very old and familiar tale.

I came across a story recently that made me think of this question of comparative folklore. I’ve been reading some very old issues of American Anthropologist in connection with a research project, and happened to come across this article by Elsie Clews Parsons. Parsons was a prolific ethnographer and folklorist of the American West during the first half of this century, a significant anthropological theorist, and the first female president of the AAA in 1941. In this article, written near the beginning of her career, she repeated a story that she had heard from an elder of the A:shiwi, or Zuni. Zuni Pueblo is an ancient and important polity in what is now the US Southwest, whose ancestry stretches through thousands of years of North American history.

The story concerns a man whose wife perished unexpectedly. In accordance with the beliefs of her people, the woman swiftly passed on to the underworld where the dead reside in peace, making new homes among their deceased kin in a place not far from the place they lived out their lives. The man, however, loved his wife deeply and could not bear the thought of their being parted, even for the course of his lifetime. He undertook a great journey, seeking out a ladder that could take him deep into the bowels of the earth and through to the underworld itself. Once there, he begged the guardians of the underworld to allow his wife to return with him to the living world. They replied that this was possible, but only if no one cried out as they were making the return journey. Joyous, the man and his wife began the return journey up the ladder. Unfortunately, as the woman stepped onto the very last rung of the ladder and into the daylight, an elderly woman saw the pair climbing out of the earth and cried out in terror. Immediately, the man’s wife transformed into an owl and flew away.

Some of my readers may be thinking that this story sounds a bit familiar, and not without reason; the cultures of Europe have been passing around similar stories for thousands of years. In ancient Greece, the closest to the Zuni tale is that of Orpheus, who in grief followed his wife Eurydice into the realm of Hades, the Hellenic underworld. In the most well-known version of the story, Orpheus played a lament on his lyre before the king and queen of the Underworld. He was among the most skilled musicians and poets in history, and the passion of his song moved the heart of Persephone (who though a goddess had herself been forced to move to the underworld) and she convinced her husband Hades to let Orpheus and his wife go, just this once. Hades agreed, but stipulated that what Orpheus asked was still impossible, unless he walked back to the living world with his wife behind him, not looking at her face until they both had reached the upper world. Unfortunately, just as Orpheus stepped forth into the daylight, he heard his wife cry out, and forgetting the rule that had bounded them, he turned to look at her. She faded before his eyes and was lost to him forever.

This mythos spawned a mystery religion known as Orphism, which differed from the orthodox faith in that Orphics believed in the transmigration of souls- a kind of reincarnation- which caused all humans, like Orpheus, to move back and forth from death to life in perpetuity, accumulating grief and finding relief only in the ascetic life. They also had another belief, very different from both their own contemporaries and from the Zuni: they, like the Christians who eventually followed them, believed that the dead are destined to be punished eventually for their transgressions in this life.

Perhaps this explains why at the end of the story, the fate of the wife is different- in the Greek story, the punishment for failing to follow instructions is to be returned to underworld. It is a permanent separation, never to be mended, and assumed to be a punishment in and of itself. For the Zuni, whose underworld was seen as an altogether more kindly place, the punishment for the couple’s presumption must be different from the normal fate, and she turns into an owl, flying away from her sorrowful husband forever. There are many other such signs of differences in religious perspective. It is taboo to say the name of deceased person in Zuni tradition, for instance, so it is not surprising the couple in this story is never named. The nature of the trial is different; it is mostly a test of Orpheus himself in the Greek version, and the guilt of failure falls solely on his shoulders (Plato later uses him as an example of the vice of cowardice). In the Zuni story, neither the man nor his wife are to blame, but rather the reaction of those in the living world. The return still fails, and the consequence is still enacted.

Many have commented on the similarity of the Orpheus myth to the Biblical story of Lot, whose unnamed wife was going to be permitted to flee the destruction of Sodom with him, but turned to look at the disaster and was turned into a pillar of salt in punishment. These are not the only variations on this theme; Izanagi and Izanami of Japan make a similar trip to the afterlife, as do Ix Chel and Itzamma of the Yucatan. Another North American nation, Nez Perce, tells a somewhat similar story about Coyote. In the mythology of Finland, it is a mother who goes after her son, and unlike these others, succeeds. In most of the stories recounted above, however, the ending is sad: the couple fails due to an inability to follow the rules of their deliverance. Sometimes the consequences are incredibly dire. In the Nez Perce tale, humanity is made forever mortal because of Coyote’s failure to return from the underworld with his wife, which task would otherwise have liberated us all from death.

Perhaps it is not surprising that similar stories crop up in many places. The spousal bond is often a strong one for good or ill, and a great many grieving widows have pondered whether their loss could be assuaged. For those whose afterlife is thought to have an entrance not far from where they live, who wouldn’t wonder whether the transit from death to life could be traveled in reverse? Faith must have an answer wherever the imagination can run. So we have many stories of the bereaved making the attempt and failing, or in the Finnish case, succeeding only after undergoing a trial so horrifying as to be questionably worth the reward. In all these tales, the supernatural guardian or guardians are kindly inclined toward the hero, but the actual deed of deliverance requires a trial, a test of will. In the European versions, the protagonist fails, and the deceased pays the price. In the Zuni version, it is another person who foils the effort, though still one of the Zuni. Either way, the failure to transcend death is, in the end, a failure of will on the human end, not an irrevocable condemnation by the divine world. This may carry a disturbing moral: Do we truly believe that our mortality is in some sense our own doing?

But this is only one interpretation, and the beauty of a folk tale is that it is interpreted anew by every storyteller and every listener, while weaving a pattern of memory and experience far into our communal history. When we look across cultures, we can weave even more complicated patterns, and find new meanings to some very old stories. Perhaps, in essence, the whole field of comparative ethnology is engaged in much the same project. If that is the case, our discipline’s collective love for a good folk tale is not hard to understand.

Is the Arab Spring a Muslim Question? Geertz on Religion, Society, and History

The following is a very partial review of Clifford Geertz’ “Islam Observed”; actually, just some remarks on his introductory chapter. I had occasion to read the book not long ago, as I was preparing a paper on religion in Indonesia in graduate school, and this is one of the classics on the subject. Clifford Geertz is a figure who looms large in the anthropology of the last half century. Most people know him for his championing of thick description in ethnography, a style of writing that emphasizes extremely detailed and introspective observations of single events and places, such as his very well known “Notes on a Balinese Cockfight”, in which the careful relaying of an illicit cockfight is Geertz’ door into explanation of the character of Balinese culture. Because he was working in Indonesia, Clifford Geertz was also one of the first anthropological observers of Islam, before the anthropological (as opposed to sociological) study of the major faiths had become commonplace. This is represented in “Islam Observed”, a comparative ethnographic look at Morocco and Indonesia respectively, two very different Islamic cultures, then as now.

Geertz, whose main interest at the time was in social change, comments on the difficulty of figuring out even where to look in order to find the religious experience. He suggests that the academic focus on uncovering the basic structures and mechanisms of religion has little utility in the field, where religion is a contextual aspect of life, difficult to unravel from other elements of philosophy, practice, and political action. “The problem,” he writes, “is not to define religion but to find it.” He names it the most nebulous factor in social change, comparing it to the more solid frames of analysis for economic and political change. Commentators looking to explain the role of faith in recent events such as the fall-out of the Arab Spring may sympathize; because Westerners have a tendency to write their own stories into news events, but we lack narratives to really describe what is happening in Egypt and Syria, dramas as closely knit into the particular history of those nations as to the global trends and movements on which they are often blamed. Said commentators would find no comfort in Geertz’s analysis, however. In fact, he explicitly denies that there is a one-to-one relationship between politics and religion, insisting that the real relationship between the two is much more subtle. Since he wrote this book, political Islamism has become a much more potent element in global politics, and his views may come across a bit naive to a modern reader. If major political parties, as in Egypt, claim religion to be their major motivation, doesn’t that make their political actions de facto representative of their religious beliefs?

To Geertz, though, what religion says in the press, or what is said of it, is less interesting than what religion means to people. Thick description means looking at things from the bottom up, starting not at the conflicts between nations, but from people’s lives and religions. To some extent, I think he is right to banish politicized religion to a superstructure of faith, rather than treating it as a structure itself. One’s political situation is not irrelevant to one’s faith, but it doesn’t control it either. Most people, when it comes down to it, have a much more personal and dynamic relationship with the religious dialogues they participate in, and even for those who value conformity greatly, the connection between idea and action is not simple in either direction. “Being Christian” or “being Muslim” does not create any necessary political orientation, nor does the political situation necessitate any particular faith structure; a fact, that for Geertz, is well represented by the fact that although his case study subjects of Morocco and Indonesia could be seen as broadly belonging to the “Muslim World”, that’s pretty much where their cultural similarities end. He writes that “their most obvious likeness … is their religious affiliation; but it is also, culturally speaking, their most obvious unlikeness.” Even the form of faith in the two countries is not obviously similar. Hierarchy is understood differently. Faith is understood differently.

So to explore the subject of religion, Geertz employs two strategies. One is to look at the role of faith in human lives, regardless of the political “container” we find ourselves in. To him, the search for religion is rooted in a search to understand the social maintenance of communal faith. He was looking for the ultimate subject of religion in a person’s life; very different than a search for the results of faith, and I find this commendable. Personal faith is “the steadfast attachment to some transtemporal connection of reality”, somewhat of an egg-heady way of saying that faith is your personal connection to a truth that lends a structure to the universe. Faith ultimately helps us “make sense” of things by placing them in a wider context, whether that context is the fallout out between conflicts on Mt Olympus or the endless contest between angels and demons. Geertz feels it is critical to distinguish between the subject of faith and its social effects, lest the two become confused. There’s a difference between observing that “The Islamic country of Iraq is in a state of religious warfare” and saying that “Islam is about religious warfare”, a difference that should be obvious but is often blurred in written and visual media, even by those who ought to know better. To make blanket statements about what “Islam” is doing in the crisis areas of the modern world is to be very sloppy about what one is saying, and in a way that is rather insulting to someone who claims the same faith label but does not subscribe to the narratives that are being attached to it, whether from within or without. For someone who is a Muslim but has no violent political aspirations (That is, most Muslims in most places statistically speaking), a statement by a political commenter that a group’s motivations are rooted in Muslim faith is at best personally meaningless, and often quite insulting and offensive.

That said, we are not independent agents, and we respond to challenges in the earthly political realm partly according to what we think about cosmology and the afterlife. “What happens to faith,” Geertz asks, “when its vehicles alter?” Faith is sustained by social structures, whatever its origin, and the faith if individual people cannot ignore the cultural dialogue that surrounds it. This is, in fact, why the faith of Indonesia is so very different from the faith of Morocco despite bearing the same name. The two nations have different cultures and historical trajectories, and this has wide ranging impacts on religious language, ritual, communal identity, and political impact. He treats religion and politics as elements evolving next to one another in the communal consciousness of a culture, neither independent of the constraints of the other nor defined by them.

This results, necessarily, in a very strong emphasis on history. The remainder of the chapter is given to describing the distinct sociopolitical histories of his two subjects, and the remainder of the book continues to refer to them often. This is slow, careful ethnography, and the historical focus represented here is something that is coming back into vogue these days in some quarters of the field. One of the central dogmas of the political ecology school of thought is that temporal and spatial context can never be safely ignored: even things that look similar when viewed from afar, can look very different when you zoom in.

As such, while it may sound good to talk about an “Arab Spring”, that movement is only part of complex architecture that contains real human lives, and the people therein change it as much as it changes them. The Syrian revolution is a Syrian revolution, and even where religion or the politics of despotism or some other factor seem to build bridges of similarity, they are only one voice in a continually unfolding story of personal and social meanings. Beware deterministic models of what will happen, when based on events thousands of miles away from each other, whether those models are built on economic theory or ethnic identity, or yes, even on religion. Ultimately, a person’s story will be their own, and a society’s story will be its own, with the larger structures of faith and politics no more defining of it than the genre in which an author is writing would be. This doesn’t mean that religion can be safely ignored. But it does mean that it can only ever be one factor in a social analysis. If human culture were an artist’s pallette, religion would determine many of the major colors present, but the decisions that humans make in light of particular social and historical factors will determine when and how those colors are used.

Notes on an Alabama Sam’s Club

How a modern dispute created a useful lesson in stratigraphy

In 2009, the city of Oxford, Alabama made the decision to level an archaeological site in favor of constructing a new mega-store in the same place. Indeed, the dirt from the bulldozed Mississippian mound was used as fill to build the foundation for the new building. Though many archaeologists protested the action, the mayor of the town believed that his detractors exaggerated the importance of the mound and that, in his own words, the proposed store would be “more prettier” than the mound that it was replacing. A report by the University of Alabama recently reinvigorated the controversy, as it emphasized the cultural importance of the site and confirmed that it was man-made. This has not led to the abandonment of the construction project, and the store is expected to open in 2014. Along with the recent revelation that a pair of Peruvian developers demolished a protected Inca pyramid, this has created quite a buzz of people talking about archaeology and the importance of preservation, lately.

However, I thought it might be interesting to use the Sam’s Club site as an example to talk about another subject in archaeology, one that is very important to the day-to-day work of archaeologists in the field. Stratigraphy is the study of geological layers and how they are deposited. The study of stratigraphy goes back to a fellow named Nicolas Steno, who in the 17th century made significant contributions to anatomy, geology, and theology, a Renaissance man in true spirit. Among these contributions were a set of observations he made about the deposition of rock layers, which were later called Steno’s Laws (or Principles) of Stratigraphy. These took the abstract observations he had found in Roman literature and transformed them into a tool that a scientist could use in the field to reconstruct the past. I’m going to focus on three of these (there are actually more, but as there are no volcanic intrusions into the Sam’s Club site as far as I know, I’m focusing here on the three that are usually taught to archaeology students)

- The Law of Superposition. New things are almost always deposited on top of old things, building up over time. Because of this, if you are looking at a sequence of layers deposited one atop another, it is generally safe to assume that the oldest one is on the bottom, and the newest on the top. (“super” means “over” in Greek)

- The Law of Original Horizontality. Gravity being the powerful force that it is, materials are generally laid down in flat layers, parallel to the sky. When things aren’t flat, time and erosion does their best to flatten them. Unless volcanism or faulting manage to tilt layers already deposited, we expect to find exactly horizontal layers under the ground.

- The Law of Lateral Continuity. It is the nature of deposition that things tend to spread out evenly and horizontally until they hit some kind of boundary, generally the valley or basin that sediment is being deposited into. If one finds the same layer in more than one place, therefore, you can generally assume that they were originally continuous (that is, they were touching) and lateral (at the same elevation) to each other .

When archaeology was leaving its infancy and becoming a real science, it was realized that a very thorough understanding of stratigraphy was needed. An archaeological site generally has layers as well, both the natural geological layers it is situated in, and the layers of occupation that we ourselves lay down. Humans tend to occupy the same places over and over throughout history, so a single site can have dozens of human-deposited layers (sometimes called archaeostrata) buried within it; the city of Paris for instance has historical plumbing projects, medieval crypts, dark age villages, Roman military camps, and many other older layers of occupation buried beneath its storied streets.

If we think about the proposed Sam’s club as a future archaeological site, we can see how a hypothetical future archaeologist might be confused if she were trying to use Steno’s Laws as the primary basis for interpreting her site. In a normal depositional environment such as a stream or lake bed, the layers would be neat and orderly, as indeed the natural strata are throughout much of the American South. At this site, however, material was first removed from its original context to build the mound in the first place, 2000 years ago, and now is being removed again for yet another construction. In the process, all three of Steno’s guidelines have been made into exceptions:

- The mound was already an unnatural feature, and we do not now know what the original depositional environment might have been (though a sedimentologist might help us to identify it). But it would have had a archaeostratigraphy generated by its construction over time. By removing the upper layers of the mound progressively, the builders have effectively reversed the order of these layers. Instead of the oldest soils being on the bottom, they are now on top, exactly contradicting the first law. (Though it is a much slower process, this can happen in geological sites as well due to faulting and folding). Our situation could be even more head-scratchingly confusing, if the original mound-builders excavated their material in a similar fashion, leaving our sediment twice inverted and facing roughly right-side up again, but with half of the archaeostrata upside-down!

- As far as original horizontality is concerned, all bets are off when we are talking about man-made hills. While most things we build are relatively horizontal, they aren’t necessarily deposited that way; it may well be that the builders are filling in ditches, building walls outward, and otherwise making deposits in a non-linear fashion that might heavily compromise our ability to understand stratigraphy within the site. In this case, the whole motivation for taking the mound’s dirt in the first place, aside from clearing space, was to level an uneven surface and raise up certain parts of the property in an attractive architectural fashion.

- Original lateral continuity is still safe to assume, but our site is certainly no longer bounded by the natural restrictions of deposition; our sediments are being physically picked up and carried far beyond the place where they were originally or even secondarily deposited. Geological history is full of blocks of sediment getting carried around by various processes, one of the reasons why this rule was needed in the first place. We need to consider, though, that archaeostrata such as building foundations and mounds are not compelled to follow this rule- they aren’t necessarily horizontal or lateral to one another, and they definitely are not confined by a basin. Because of this, they are going to look and behave differently in a stratigraphic profile.

Does this mean that stratigraphy is not useful in archaeology? Of course not! For one thing, Steno’s laws do hold for the original depositional environment, where the sediments which compose both mounds were formed. This gives us a baseline for comparison when we are trying to interpret what we are looking at. They also give us a hint at what may have happened after the two sites were formed. Just as a geologist knows that a sudden vertical disruption in an otherwise horizontal layer might indicate a fault, an experienced archaeoIogist can look at an exposure and instantly know where the human alterations of that layer (what we call features) are probably located, just by noticing where the horizontal layers have breaks. Even without excavating them and finding out exactly what they are, or seeing something an obvious artifact sticking out, they know that something must have happened in that spot to disrupt the layers. For a contract archaeologist, who very quickly needs to assess a situation while removing as little material as possible, such a tool is invaluable. Indeed, the nature of the mound’s stratigraphy is one reason that the archaeologists assigned to the case know for certain that it is of human origin rather than, as the city claims, a natural feature of some kind.

For the rules of stratigraphy to be useful, though, it is just as important to consider just how much a handful of dedicated humans can do to disrupt an otherwise uncomplicated stratigraphic situation. Even before the advent of bulldozers and earthmovers, we have been remarkably effective re-shapers of the world we live in, and the parts of the world we have occupied longest seem to follow almost a separate set of rules. Learning the rules of human stratigraphy is a critical step toward interpreting site formation, and is the most common application of geological principles to anthropological subjects. This study has had a profound impact on archaeology, but has also impacted the way cultural anthropologists think about landscapes and how humans interact with them generally.

The Dead Man at Grandview Point

Recently I had the privilege of traveling through the American Southwest with a cadre of geology students from the college where I teach, and I was thinking about this blog as we traveled. It’s hard to see in advance where a long-term project like a blog might end up, and I’ve come up with at least a dozen or so very different ideas about it in the two years or so since the name “Homonculus” popped into my head and demanded recognition. I’ve been wanting to start a general-purpose anthropology blog for some time, but you do need more to go on than just a vague subject if something is going to work. Homonculus is meant as a playground for talking about the ideas that make my discipline compelling to me: learning to interpret humanity from the evidence at hand- evidence that is at once all around us and extremely difficult to synthesize and understand. Anthropology is famous (perhaps infamous at times) for walking the boundary between science and the humanities. This is because it has to. We’re complex creatures, and cannot step outside of the hazy world of subjectivity, because a human being is always a subject. At the same time, an anthropology without science is blind, because any project of understanding humans is inundated with data and assumptions, some of them obviously false and others just plain difficult to puzzle out.